Leonardo Fibonacci died over 760 years ago but he had a profound effect on mathematics in western civilization. He brought what he had learned from mathematician in north Africa back to Europe and authored the book Liber Abaci, which described such things as the Hindu-Arabic numeral system and place value of numbers. In the book he also showed how a number of mathematical problems were solved using the techniques he had learned, one of which was the growth of a population of rabbits. Although he didn't invent it, that sequence bears his name today, and is seen in many places in nature.

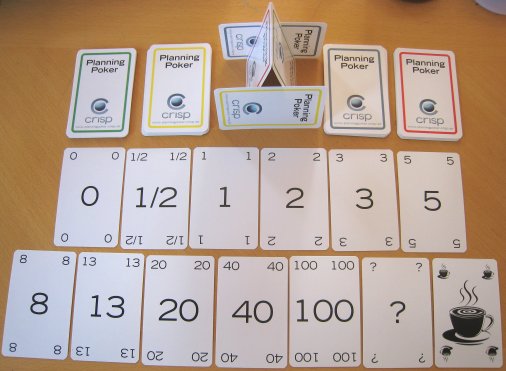

The use of the Fibonacci sequence in a slightly modified form has also been popularized in the Agile community as values which can be used to estimate the effort required to deliver work. This is usually tied to the Planning Poker technique created in 2002 by James Grenning, and Mike Cohn's Mountain Goat Software sells decks of planning poker cards that use the values 0, 1/2, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40, 100, ? and infinity.

If you look, though, at James' paper and Mike's excellent 2005 book Agile Estimating and Planning, they both make a very similar point. From James:

Why is that? Well, I'm going to borrow a famous acronym from the Extreme Programming world: YAGNI... You Ain't Gonna Need It!

Yes, Mike's card decks have many more values. I suppose that a deck with 5 values and infinity would be somewhat less attractive to buy, but the real point is how much damage is being caused by teams using values of 13, 20, 40 and 100? Do those numbers really mean anything?

I assert that they are meaningless, and actually cause much more harm than good. The harm comes from 2 sources. First, it allows teams to get away with not splitting work down into pieces that can be estimated reliably. Second, and as a consequence of the first, by providing inaccurate estimates for very large things teams/product owners/stakeholders can have a false sense of security about how much effort will be required. Estimates that are wildly inaccurate will lead to incorrect decisions about whether to proceed with some work or not. The smaller the piece of work being estimated, the higher the probability that the estimate is accurate enough to make reasonable decisions.

The Curse of Choice

Having too many choices is actually a curse, and limiting the choices available for teams to use for estimation forces them to really think hard about breaking the work down. I personally have used the four values of 1, 2, 3 and "too big" with good success over the years, but I can certainly live with what James and Mike suggest above.

To go a step further, though, we should be applying Lean thinking and strive to eliminate the variability of the size of work completely. This would mean that all items are broken down until they're the same size, obviating the need for any estimation at all! That's a perfection vision that very few people have achieved, although it has happened.

In the end, we need to move away from using the longer modified Fibonacci series as if it were a law of nature. Being modified, it really isn't a law, and actually provides very little value beyond the number 8.

Within Agile teams, Fibonacci must die!

The use of the Fibonacci sequence in a slightly modified form has also been popularized in the Agile community as values which can be used to estimate the effort required to deliver work. This is usually tied to the Planning Poker technique created in 2002 by James Grenning, and Mike Cohn's Mountain Goat Software sells decks of planning poker cards that use the values 0, 1/2, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40, 100, ? and infinity.

If you look, though, at James' paper and Mike's excellent 2005 book Agile Estimating and Planning, they both make a very similar point. From James:

As the estimates get longer, the precision goes down. There are cards for 1,2,3,5,7,10 days and infinity. This deck might help you keep your story size under 2 weeks. Its common experience that story estimates longer than 2 weeks often go over budget. If a story is longer than 2 weeks, play the infinity card and make the customer split the story.From Mike's Agile Estimating and Planning (pg. 52):

Because we are best within a single order of magnitude, we would like to have most of our estimated in such a range. Two estimation scales I've had good success with are:In both of these cases, James and Mike recognize that as estimate size increases accuracy decreases rapidly, and they both use a very narrow range of values that can be used for estimates.

- 1, 2, 3, 5 and 8 [Fibonacci]

- 1, 2, 4 and 8

Why is that? Well, I'm going to borrow a famous acronym from the Extreme Programming world: YAGNI... You Ain't Gonna Need It!

Yes, Mike's card decks have many more values. I suppose that a deck with 5 values and infinity would be somewhat less attractive to buy, but the real point is how much damage is being caused by teams using values of 13, 20, 40 and 100? Do those numbers really mean anything?

I assert that they are meaningless, and actually cause much more harm than good. The harm comes from 2 sources. First, it allows teams to get away with not splitting work down into pieces that can be estimated reliably. Second, and as a consequence of the first, by providing inaccurate estimates for very large things teams/product owners/stakeholders can have a false sense of security about how much effort will be required. Estimates that are wildly inaccurate will lead to incorrect decisions about whether to proceed with some work or not. The smaller the piece of work being estimated, the higher the probability that the estimate is accurate enough to make reasonable decisions.

The Curse of Choice

Having too many choices is actually a curse, and limiting the choices available for teams to use for estimation forces them to really think hard about breaking the work down. I personally have used the four values of 1, 2, 3 and "too big" with good success over the years, but I can certainly live with what James and Mike suggest above.

To go a step further, though, we should be applying Lean thinking and strive to eliminate the variability of the size of work completely. This would mean that all items are broken down until they're the same size, obviating the need for any estimation at all! That's a perfection vision that very few people have achieved, although it has happened.

In the end, we need to move away from using the longer modified Fibonacci series as if it were a law of nature. Being modified, it really isn't a law, and actually provides very little value beyond the number 8.

Within Agile teams, Fibonacci must die!

Comments

I would estimate as follows

- story = 4.5 ( really 1-8)

- epic = 30 (maybe 10-50)

- minimum marketable feature set = 130 ( maybe 60- 200)

This range has a wide variation, so it actually matters, anything finer grain is a wash, it will average out before long...

I do like the idea of simply treating items as all the same size, although in my experience the difference between a 1 and an 8 is significant enough not to be ignored.

Where I have an issue, though, is with your estimate for an epic. How do you really know that it's 30 and not smaller stories totalling 15 or 45? What value are you gaining by estimating something that coarse-grained?

What I'm saying is that you need to have broken down the items for the current release such that they are within the 1-8 (Mike) or 1-10 (James) range and the team is comfortable with those estimates. I would (and have many times) gone even further and broken them down until they are in a range of 1-3.

Any effort estimating anything bigger very quickly becomes waste owing to the gross inaccuracy. I'm OK with, "The last time we did something roughly that size it was about 10 stories and 25 points", but that would be for something outside of the current release and not used for concrete planning.

Thanks for the comment!

There is still some variability in the effort required between a one and a three, so I wouldn't arbitrarily choose to stop estimating.

I do, however, think it's a good idea to break the work down until the variation *can* be arbitrarily ignored, although I've never been able to do that in practice.

Thanks for the comment!

In order to get away from the higher values you have to have all of the current release estimated, and possibly some of the next release. That means your releases necessarily have to be relatively small, though I've used this technique for 6 month release cycles.

Are new stories introduced? Sure. Do you further break down existing stories as you learn more? Absolutely!

I do realize that this isn't Scrum canon, but that really doesn't concern me. I came from the XP world anyway. ;)

I think a lot of agilists have been shortening the scale for years, and asking for most stories to be implemented in 1-to-4 point increments. This biggest hurdle is often just a matter of getting Customer/PO to visualize small increments instead of complex, completed features.

I suppose it's the value of seeing releases as short-term things that makes Lean Startup and similar strategies so valuable to business. It just happens to represent a pretty big change in the process behind the product vision.

Yes, "must be truncated" gets a lot less attention than "must die"! :)

Over my '10 years of Agile' I've seen estimation techniques ranging from Ron & Chet's "just make them all the same small size and forget estimating" to "estimate everything in ideal person-days".

Where I have consistently seen issues is when time-based estimated are used and where there are too many choices for those estimating. The former creates a subconscious (and sometimes conscious) commitment to calendar time, and the latter has the issues I detailed in the post.

Allowing more values just masks other issues such as not spending the time to break the work down smaller.

Thanks for the comment!

So the business plan is based on fiction then? Serious question.

I understand that most business don't yet subscribe to more modern approaches such as Beyond Budgeting and the even newer Lean Startup Innovation Accounting concept, so you need to determine how much something is going to cost. Well, what's the largest component of the cost of delivering a project or product? The people. That cost isn't going to change much, regardless of what epics are in the backlog. Remember that Agile very much prefers long-lived teams... so what does the team cost per month or year? What capital costs do you need to factor in? The only possible value in estimating large items well outside of the current release is to determine if there's enough work for the team in the future. Even then, you're taking a 1000 yard shot at a rabbit using a handgun... in theory you could get lucky and hit the rabbit, but you're much more likely to be so far off target as to be laughable.

So why bother wasting that time in the first place?

On my lean island, the demand was easier to cope with, so I gradually came to need only one size. The lead-time distribution chart showed two clusters (2:1 ratio), but the cluster where an item would end up didn't always match the initial estimate. Not a problem as the lead time was short enough. Using Jeff Anderson's math above, everything was size 1.5! I found "Is this item acceptable to its proposed class of service?" to be the key question. If not, play any card of a red suit and break up the item.

Back on the Scrumbut mainland, my observation is that the most damaging card in the Fibonacci deck is a 40. It approximates the number of hours in a workweek. I know teams that use mostly high-point cards and are unable to get over the hurdle of relative-size estimation.

Thanks for your great comment! That's a fantastic explanation of evidence-based planning, and I wish there were more teams that would inspect & adapt their way towards it!

I do think though that a longer sequence of numbers allows for a false sense of precision in the estimates and that is a good enough reason to move to t-shirt sizes or some other low resolution approach.

BR

Morgan